Zulu (1964 film)

| Zulu | |

|---|---|

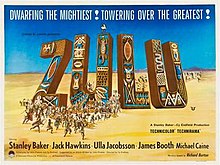

UK cinema release poster | |

| Directed by | Cy Endfield |

| Screenplay by | John Prebble Cy Endfield |

| Story by | John Prebble |

| Produced by | Stanley Baker Cy Endfield |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Richard Burton |

| Cinematography | Stephen Dade |

| Edited by | John Jympson |

| Music by | John Barry |

Production company | Diamond Films |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 139 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$ 1,720,000. (666,554. GBP)[2] or £653,439[3] |

| Box office | $8 million (US)[4] |

Zulu is a 1964 British epic historical drama film depicting the 1879 Battle of Rorke's Drift between a detachment of the British Army and the Zulu, in the Anglo-Zulu War. The film was directed and co-written by American screenwriter[5] Cy Endfield. He had moved to the United Kingdom in 1951 for work after being blacklisted in Hollywood. It was produced by Stanley Baker and Endfield, with Joseph E. Levine as executive producer. The screenplay was by Endfield and historical writer John Prebble, based on Prebble's 1958 Lilliput article "Slaughter in the Sun".

The film stars Stanley Baker and introduces Michael Caine in his first major role, with a supporting cast that includes Jack Hawkins, Ulla Jacobsson, James Booth, Nigel Green, Paul Daneman, Glynn Edwards, Ivor Emmanuel, and Patrick Magee. Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi (a future South African political leader) played Zulu King Cetshwayo kaMpande, his great-grandfather. The opening and closing narration is spoken by Richard Burton.

First shown on the 85th anniversary of the battle, 22 January 1964, at the Plaza Theatre in the West End of London, Zulu received widespread critical acclaim, with praise for its sets, soundtrack, cinematography, action sequences, and the cast's performances, particularly Baker, Booth, Green, and Caine. The film brought Caine international fame. In 2017, a poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers, and critics for Time Out magazine ranked it as the 93rd best British film ever.[6]

Plot

[edit]In January 1879, in the aftermath of the crushing defeat of a 1,300-man British column by the Zulu armies at Isandlwana, Zulu warriors scavenge the battlefield and collect rifles and ammunition from the dead soldiers. At a mass Zulu marriage ceremony witnessed by missionary Otto Witt and his daughter Margareta, Zulu King Cetshwayo is informed of the great victory. Witt and Margareta flee to their missionary station when they realise that the Zulu are going to attack the remote outpost at Rorke's Drift in Natal. A company of the British Army's 24th Regiment of Foot are using the station as a supply depot and hospital for British forces in Zululand.

Receiving news of Isandlwana from Natal Native Contingent Commander Adendorff and warnings that a force of 4,000 Zulu warriors are advancing on their position, Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers assumes command of a force consisting of some 150 men, 30 of whom are sick and wounded, as he is slightly senior to their nominal commander, Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead. With not enough time to order a full evacuation, Chard decides to stay and fight. He has wagons, sacks of mealie (maize), and crates of hardtack stacked to form a defensive perimeter, gun holes knocked in the hospital walls, and a medical ward set up in Witt's chapel. A contingent of South African cavalrymen from Isandlwana arrive, refuse Chard's pleas to help reinforce the station on the grounds that it is hopeless, and swiftly depart on their horses. Enraged by Chard arming the hospital's patients and ordering them to fight instead of allowing them to be evacuated, the minister Witt persuades the Zulus serving in the Natal Native Contingent to desert. Chard orders the wagons to be overturned to plug gaps in the barrier and orders for Witt to be locked in the chapel's supply room.

The Zulu impis approach and charge but quickly retreat under British fire; Adendorff explains that they are trying to find weak points in the station's defences. Witt starts drinking heavily and proclaims that none of the soldiers will survive the coming battle. Chard permits Margareta to take her father away; the Zulus let them pass. Chard is concerned that the northern perimeter wall is under-defended and realises that the Zulus, aware of this, are preparing to attack the station from all sides. Zulus armed with British rifles start firing at the soldiers. Throughout the day and night, wave after wave of Zulu attackers are repelled, but some defenders are killed and wounded. The hospital's hay roof catches fire and the whole building is engulfed; Private Henry Hook rallies the patients to fight attacking warriors and escape. Sergeant Robert Maxfield, Hook's mentally broken commanding officer, is killed as the hospital burns down.

The next morning, a large number of Zulus approach to within several hundred yards and sing a lament for their dead before launching again into their war chant. The British respond by singing the Welsh song "Men of Harlech". In the final assault, just as it seems the Zulus will finally overwhelm the defenders, the British soldiers fall back to a small redoubt in front of the chapel. With a reserve of men hidden within the redoubt, they form into three ranks and fire volley after volley, inflicting heavy casualties; the Zulus retreat. After a pause of three hours, the Zulus re-form on the Oscarberg. Resigned to another assault, the British are astonished when the massed Zulu sing a song to honour the defenders' bravery and depart. The exhausted British begin recuperating as Chard plants a Zulu shield in the ground.

Cast

[edit]- Stanley Baker as Lieutenant John Chard, an officer serving with the Royal Engineers, assigned to build a bridge nearby. He takes charge of the defence of Rorke's Drift by virtue of slight seniority in his commission date.

- Michael Caine as Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, an upper-class officer who yields to Chard's command. He is inexperienced, arrogant, and dismissive of the Zulu army's capabilities, but slowly comes into his own by following Chard's example and proves to be courageous.

- Jack Hawkins as Reverend Otto Witt, a Swedish missionary based at Rorke's Drift.

- Ulla Jacobsson as his daughter Margareta Witt

- Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi as King Cetshwayo; Cetshwayo was Buthelezi's maternal great-grandfather

- James Booth as Private Henry Hook, described as "a thief, a coward, and an insubordinate barrack-room lawyer", who has been confined to the hospital after falsely claiming sickness to get excused from his duties. He redeems himself and proves himself to be an excellent soldier in his defence of the hospital.

- Nigel Green as Colour sergeant Frank Bourne, a seasoned NCO who plays a key role in organizing and leading the British defence.

- Paul Daneman as Sergeant Robert Maxfield, Private Hook's bedridden and mentally broken commanding officer.

- Joe Powell as Sergeant Joseph Windridge

- Ivor Emmanuel as Private Owen, a Welsh baritone and head of the company choir.

- Glynn Edwards as Corporal William Allen

- Neil McCarthy as Private Thomas, Owen's best friend who longs to return to his farm in Wales

- David Kernan as Private Frederick Hitch

- Gary Bond as Private Cole

- Peter Gill as Private 612 John Williams, a member of the company choir assigned to the squad defending the hospital.

- Richard Davies as Private 593 William Jones

- Denys Graham as Private 716 Robert Jones

- Patrick Magee as Surgeon-Major James Henry Reynolds

- Dickie Owen as Corporal Frederick Schiess, a hospitalised Swiss corporal in the Natal Native Contingent who volunteers for Chard's defenders

- Gert van den Bergh as Lieutenant Gert Adendorff, an Afrikaner officer serving with the Natal Native Contingent and one of the few survivors of the battle at Isandlwana. He advises Chard and fights alongside him

- Dennis Folbigge as Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton

- Larry Taylor as Hughes

- Kerry Jordan as Louis Byrne, the company cook who is forced to join the defenders despite his pleas of cowardice.[8]

- Harvey Hall as Sick Man

Production

[edit]

Cy Endfield was inspired to make the film after reading an article on the Battle of Rorke's Drift by John Prebble. He took it to actor Stanley Baker, with whom he had made several films and who was interested in moving into production. Endfield and Prebble drafted a script, which Baker showed to Joseph E. Levine while making Sodom and Gomorrah (1962) in Italy. Levine agreed to fund the movie, which Baker's company, Diamond Films, produced.[9] It was shot using the Super Technirama 70 cinematographic process, and distributed by Paramount Pictures in all countries excluding the United States, where it was distributed by Embassy Pictures.[5]

Most of Zulu was shot on location in South Africa. The mission depot at Rorke's Drift was recreated beneath the natural Amphitheatre in the Drakensberg Mountains. (This landscape was more precipitous and dramatic than the real Rorke's Drift, which is little more than two small hills). The set for the British field hospital and supply depot was created near the Tugela River with the Amphitheatre in the background. The real location of the battle was 100 kilometres (60 mi) to the northeast, on the Buffalo River near the isolated hill at Isandlwana.

Other scenes were filmed within the national parks of the then Province of Natal. Interiors and all the scenes starring James Booth were completed at Twickenham Film Studios in Middlesex, England. The majority of the Zulu warriors were real Zulus. The 240 Zulu extras who were employed for the battle scenes, were bused in from their tribal homes more than 100 miles away. Around 1,000 additional tribesmen were filmed by the second unit in Zululand. Eighty South African military servicemen were cast as soldiers.[10]

The film was compared by Baker to a Western movie, with the traditional roles of the United States Cavalry and Native Americans taken by the British and the Zulu, respectively. Director Endfield showed a Western to Zulu extras to demonstrate the concept of film acting and how he wanted the warriors to conduct themselves.[5]

It has been rumoured that due to the apartheid laws in South Africa, none of the Zulu extras could be paid for his performance. Endfield was said to have circumvented this restriction by leaving them all the animals, primarily cattle, that were used in the film. These are highly valued in their society. This allegation is incorrect; no such law existed and all the Zulu extras were paid in full. The main body of extras were paid the equivalent of nine shillings per day each, additional extras eight shillings, and the female dancers slightly less.[11][10]

Michael Caine, who was primarily playing bit parts at this early stage in his career, was originally up for the role of Private Henry Hook, which went to James Booth. According to Caine, he was extremely nervous during his screen test for the part of Bromhead. Director Cy Endfield told him that it was the worst screen test he had ever seen, but they cast Caine in the part anyway because the production was leaving for South Africa shortly and they had not found anyone else for the role.[5] Caine said that he was fortunate that the film was directed by an American (Endfield), because "no English director would've cast me as an officer, I promise you, not one," due to his Cockney roots. Most officers at the time were from upper-class families.[12] Caine later said "My entire movie career is based on the length of the bar at the Prince of Wales theatre, because I was on my way out [after failing to get the part auditioned for] and it was a very long walk to the door. And I had just got there, when he called out: 'Come back!'[13]

The company was unable to obtain enough historically authentic Martini-Henry rifles for all of the extras, and had to make up the difference with later Lee Enfields. These have a very noticeable moving bolt on the right side, absent on the Martini-Henry. The sidearms used were also visibly later types, World War I-vintage Webley Mk VI revolvers.[14]

The budget of the film has been the subject of some speculation. Press-related figures of $3 million and even $3.5 million[9] were mentioned upon the picture's American release. Joe Levine later revealed that Stanley Baker had approached him with a script and budget in 1962, just after filming Sodom and Gomorrah. Levine agreed to finance the picture up to $2 million. According to the records of the British completion bond company, Film Finance, Ltd., the production eventually finalized its budget at £666,554 (approximately, $1,720,000). This included a contingency amount of £82,241, of which only £34,563 had been used by the time the picture had all but wrapped post-production (Cost Report #15, 18 October 1963). This would have placed the near-final negative cost at £618,876 (approximately $1,600,000).[15]

Historical accuracy

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (March 2019) |

The basic premises of the film are true and largely accurate, but some characters are fictionalised or bear little resemblance to their real life counterparts. The vastly outnumbered British did successfully defend Rorke's Drift, more or less as portrayed in the film. Writer and director Cy Endfield consulted a Zulu tribal historian for information from Zulu oral tradition about the attack. Some events are created for dramatic effect.[5][16]

The regiment

[edit]- The film presents the 24th Regiment of Foot as a predominantly Welsh regiment, which was not the case in 1879. Of the soldiers present at Rorke's Drift, 49 were English, 32 Welsh, 16 Irish, and 22 others of indeterminate ethnicity.[17][18][19] While the regiment had been based at Brecon in South Wales for several years, its full name at the time was 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot. (In 1881, the regiment assumed its later name of South Wales Borderers.)

- The song "Men of Harlech" features prominently as the regimental song; it did not achieve that status until later. At the time of the battle, the regimental song was "The Warwickshire Lad". No "battlefield singing contest" took place between the British and the Zulu.[20]

The Witts

[edit]The historical record concerning the Swedish missionaries, the Witts, has inconsistencies, though the minister in the film is portrayed quite differently than the historical Witt. The real man was younger, married and with children, a teetotaler and not a pacifist. Otto Witt's wife and children were 30 kilometres (19 mi) away at the time of the battle. No pacifist, Witt had co-operated closely with the British Army and earlier negotiated a lease to put Rorke's Drift at Lord Chelmsford's disposal. Witt clarified that he did not oppose British intervention against King Cetshwayo. Witt had stayed at Rorke's Drift because he wished "to take part in the defence of my own house and at the same time in the defence of an important place for the whole colony, yet my thoughts went to my wife and to my children, who were at a short distance from there, and did not know anything of what was going on". On the morning of the battle, Otto Witt, with the chaplain, George Smith, and Surgeon-Major James Henry Reynolds, had ascended Shiyane (Oscarberg), the large hill near the station, and noticed the approach of the large Zulu force across the Buffalo River. Given his family at a distance, he left on horseback before the battle in order to join them.[21]

The men of the regiment

[edit]- Lieutenants John Chard and Gonville Bromhead: Chard received his commission in February 1868, before Bromhead. The latter was the junior officer and second-in-command at the Drift although he was an infantryman (who usually took command) and Chard was an engineer. The film says that Bromhead received his commission three months after Chard but, in fact, he did not receive it until three years after Chard.

- Surgeon Reynolds: During the Battle of Rorke's Drift, Reynolds went around the barricades, distributing ammunition and tending to the wounded, actions not shown in the film.[22] During the closing voiceover, he is incorrectly referred to as "Surgeon-Major, Army Hospital Corps". Reynolds was of the Army Medical Department, and was not promoted to the rank of Surgeon-Major until after the action at Rorke's Drift.[22] The pacifism apparent in Magee's portrayal is not based on the historical Surgeon Reynolds.

- Private Henry Hook, VC, is depicted as a rogue with a penchant for alcohol; in fact, he was a model soldier who later was promoted to sergeant; he was also a teetotaller. Historically he had been assigned to the hospital specifically to guard the building.[23] The real Hook's daughters were reportedly so disgusted at his portrayal that they walked out of the 1964 London premiere; a campaign was organized to have Hooks's documented historical reputation restored.[24] The film's producers said they chose Hook by chance and created the character as seen in the film, simply because "they wanted an anti-hero who would come good under pressure".[25]

- Corporal William Allen is depicted as a model soldier; historically he had recently been demoted from sergeant for drunkenness.[26]

- Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne (1854–1945) is a middle-aged, big and hardened veteran. In fact, he was of modest stature and, aged 24, the youngest colour sergeant in the British Army.[27] He was called "The Kid" by his men.[28] Colour Sergeant Bourne would not have worn medals on his duty uniform. Moreover, Green's costume has the chevrons on the wrong arm. After the battle, Bourne was offered a commission but turned it down because he lacked the money necessary to serve as a commissioned officer; he finally accepted a commission in 1890. He was the last British survivor of the Battle and a full colonel upon his death in 1945.

- Padre George Smith ("Ammunition" Smith), the chaplain, is not a character in the film, although he won a Victoria Cross for his actions.[29]

- Corporal Christian Ferdinand Schiess was 22, significantly younger than the actor who portrayed him.[30]

- The detachment of cavalry from "Durnford's Horse" who ride up to the mission station were members of the Natal Native Contingent. Historically this was chiefly composed of black African cavalrymen, rather than the purported local white farmers depicted as a kind of militia in the film. The members of the NNC were present at the opening of the battle, but left as they had very little ammunition for their cavalry carbines. Captain Stephenson is depicted at their head; in reality, he was leading the NNC infantry, which had already deserted.[citation needed]

- The uniforms of the Natal Native Contingent are inaccurate: NNC troops were not issued with European-style clothes. Only their European officers wore makeshift uniforms. The rank and file wore traditional tribal garb topped by a red rag worn around the forehead (as correctly depicted in the 1979 film, Zulu Dawn, about the battle of Isandlwana.) The story of their desertion is true. Witt left before they did. They left of their own accord, along with Captain Stephenson and his European NCOs.[31] These deserters were fired at as they left and one of their NCOs, Corporal Anderson, was killed. Stephenson was later convicted of desertion at a court-martial and dismissed from the army.[citation needed]

The Zulu

[edit]King Cetshwayo did not order the attack on the mission station, as the film suggests. Cetshwayo had specifically told his warriors not to invade Natal, the British colony. The attack was led by Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande, the King's half-brother, who pursued fleeing survivors at Isandlwana across the river and moved on to attack Rorke's Drift. Although the defenders fired almost 20,000 rounds of ammunition, just under 400 Zulus were killed at Rorke's Drift. A similar number were left behind when the Zulu retreated, as they were too badly wounded to move. Comments from veterans many years after the event suggest the British killed many of these wounded men in the battle's aftermath, raising the total number of Zulu deaths to more than 700.[citation needed]

Battle

[edit]At roughly 7 am following the day of battle, an Impi appeared, prompting the British to man their positions again. No attack materialised, as the Zulu had been on the move for six days prior to the battle. Their ranks included hundreds of wounded, and they were several days' march from any supplies.

Around 8 am, another force appeared. The defenders abandoned their breakfast and took up their positions again. The approaching troops were the vanguard of Lord Chelmsford's relief column.

The Zulu did not sing a song saluting fellow warriors and departed at the approach of the British relief column.[20][23] This sequence has been both praised for showing the Zulus in a positive light and treating them and the British as equals, and criticised as undermining any anti-imperial message of the film.[32]

Reception

[edit]On its initial release in 1964, Zulu received acclaim from critics. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that "if you're not too squeamish at the sight of slaughter and blood and can keep your mind fixed on the notion that there was something heroic and strong about British colonial expansion in the 19th century, you may find a great deal of excitement in this robustly Kiplingesque film. For certainly the fellows who made it, Cy Endfield and Stanley Baker, have done about as nifty a job of realizing on the formula as one could do."[33] Variety praised the "intelligent screenplay" and "high allround standard of acting," concluding, "High grade technical qualities round off a classy production."[34]

Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post wrote that the film was "in the much-missed tradition of 'Beau Geste' and 'Four Feathers.' It has a restrained, leisurely tension, the heroics are splendidly stiff-upper-lip and such granite worthies as Stanley Baker and Jack Hawkins head the cast."[35]

Whitney Balliett of The New Yorker wrote that the film had "not only refurbished all the clichés of the genre but given them the sheen of high style ... It has already been pointed out that 'Zulu' is in poor taste. But so are such invaluable relics as G. A. Henty and Rider Haggard and Kipling."[36] The Monthly Film Bulletin called Zulu "a typically fashionable war film, paying dutiful lip service to the futility of the slaughter while milking it for thrills. And the battle, which occupies the whole second half of the film, is unquestionably thrilling ... But whenever there is a pause in the action the script plunges relentlessly into bathos, with feuding officers, comic other ranks, and all the other trappings of British War Film Mark I, which one had hoped were safely obsolete."[37]

Caine's performance won him praise from reviewers. His next film role would be as the star of The Ipcress File, in which he was reunited with Nigel Green.[5]

The film was one of the biggest box-office hits of all time in the British market. For the next 12 years, it remained in constant cinema circulation before its first television appearance. It became a television perennial and remains beloved by the British public.[10]

Rotten Tomatoes gives a score of 96% based on reviews from 27 critics. The consensus summarizes: "Zulu patiently establishes a cast of colorful characters and insurmountable stakes before unleashing its white-knuckle spectacle, delivering an unforgettable war epic in the bargain."[38]

Among more modern assessments, Robin Clifford of Reeling Reviews gave the film four out of five stars, while Brazilian reviewer Pablo Villaça of Cinema em Cena (Cinema Scene) gave the film three stars out of five.[39] Dennis Schwartz of Ozus Movie Reviews praised Caine's performance, calling it "one of his most splendid hours on film" and graded the film 'A'.[40]

When released in Apartheid South Africa in 1964, the film was banned for black audiences (as the government feared that its scenes of blacks killing whites might incite them to violence). The government allowed a few special screenings for its Zulu extras in Durban and some smaller Kwazulu towns.[41]

By 2007, critics were polarised over whether the movie was anti-imperialist or racist.[32]

Chris McEneany gave the film 8 out of 10 stars.[42]

In 2010, Alex von Tunzelmann of The Guardian gave the film a grade of B, saying: "The Zulus are a mystery, the Welsh are misplaced, a Victoria Cross recipient is slandered, and no one has enough facial hair. Nonetheless, Zulu is a brilliantly made dramatisation of Rorke's Drift, and it does a fine job of capturing the spirit for which the battle is remembered."[43]

In 2014, Pat Reid of Empire gave the film four out of five stars, describing Zulu "As a spectacular war film with a powerful moral dimension…Like the defence of Rorke's Drift itself, its legend grows with the passing of time."[44] Cinema Retro released a special issue dedicated to Zulu, which detailed the production and filming of the film. Stating that the film "has lost none of its impact over the years", it praises the battle sequences, calling them "impressively staged" and the portrayal of the Zulus "as noble figures who develop a mutual respect for the British, even as they are trying to kill them". It also praises the "particularly impressive" performances of the supporting cast of Hawkins, Jacobbsson, and Magee.[45]

In a Telegraph article, Will Heaven wrote, "Zulu is a story of real-life heroism seen through the lenses of Victorian propaganda and Hollywood epic cinema. It may not be truthful – but, my God, the result is thrilling."[46]

In regards to the film's attitudes on race, author Daniel O'Brien noted one of the Zulus killing one of their own to protect Witt's daughter, and how Bromhead dismissing the native auxiliaries who died with the column at Isandhlwana, "Damn the levies man – more cowardly blacks", is reprimanded by Adendorff.[47]

In 2018, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi defended the film's cultural and historical merits, stating that there's a "...deep respect that develops between the warring armies, and the nobility of King Cetshwayo's warriors as they salute the enemy, demanded a different way of thinking from the average viewer at the time of the film's release. Indeed, it remains a film that demands a thoughtful response."[48] Buthelezi, with whom Baker had become friends with during production, described Baker as "the finest white man he had ever met".[49]

Awards and honours

[edit]Ernest Archer was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Colour Art Direction on the film.[5] The magazine Total Film (2004) ranked Zulu the 37th greatest British movie of all time, and it was ranked eighth in the British television programme The 100 Greatest War Films.[50] Empire magazine ranked Zulu 351st on their list of the 500 greatest films.

Presentation format

[edit]Zulu was filmed in Technirama and intended for presentation in Super Technirama 70, as shown on the prints. In the UK, however, the only 70mm screening was a press show prior to release. While the vast majority of cinemas would have played the film in 35mm anyway, the Plaza's West End screenings were of the 35mm anamorphic version as well rather than, as might have been expected, a 70mm print. This was due to the UK's film quota regulations, which demanded that cinemas show 30% British films during the calendar year, but the regulations only applied to 35mm presentations. By 1964, the number of British films available at cinemas like the Plaza could be limited, and Zulu gave them several weeks of British quota qualification if they were played in 35mm. In other countries, the public got to see films in 70mm.

Home video releases

[edit]In the US, a LaserDisc release by The Criterion Collection retains the original stereophonic soundtrack taken from a 70mm print.

An official DVD release (with a mono soundtrack as the original stereo tracks were not available) was later issued by StudioCanal through Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The film was released on Blu-ray in the UK in 2008; this version is region-free. On 22 January 2014, the 50th anniversary of the film and the 135th anniversary of the actual battle, Twilight Time issued a limited-edition Blu-ray of Zulu in the US with John Barry's score as an isolated track.[51][52]

Merchandising

[edit]- A soundtrack album by John Barry featuring one side of the film score music and one side of "Zulu Stamp" was released on Ember Records in the UK and United Artists Records outside the Commonwealth.

- The choreographer Lionel Blair arranged a dance called the "Zulu Stamp" for Barry's instrumentals.[53]

- A comic book by Dell Comics was released to coincide with the film that features scenes and stills not in the completed film.[54][55][56]

- Conte toy soldiers and playsets decorated with artwork and stills from the film were produced.[57]

Prequel

[edit]Endfield later wrote Zulu Dawn (1979), a prequel to the original film, depicting the Battle of Isandlwana. The battle's aftermath was shown at the start of the first film.

In popular culture

[edit]- The Battle of Helm's Deep sequence in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers was filmed in a manner deliberately reminiscent of Zulu.[58]

- Blood Bath at Orc's Drift is a 1985 campaign supplement for the Games Workshop Warhammer Fantasy Battle (2nd edition) game, which pitted a small force of High Elves, Dwarfs, and Humans against an attacking army of Orcs. In 1997, Games Workshop again drew inspiration from Zulu for the Massacre at Big Toof River. In this event, Praetorian Guards, a faction based directly on late-19th century colonial English forces, faced off against Orc attackers, filling the role of the Zulus.[59][60]

- Stanley Baker purchased John Chard's Victoria Cross in 1972, believing it to be a replica. After Baker's death, it was sold to a collector at a low price but found to be a genuine medal.[61]

- Afrika Bambaataa said that he chose the name "Zulu" based on inspiration from the 1964 film. What Bambaataa "saw in Zulu, were powerful images of Black solidarity." This would later inspire the name for his organisation, Universal Zulu Nation, in the 1970s.[62]

See also

[edit]- BFI Top 100 British films (1999)

- Cape Colonial Forces

- Colony of Natal

- Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet

- Henry Herbert, 4th Earl of Carnarvon

- History of Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899

- Kaffir (Historical usage in southern Africa)

- British Kaffraria

- Kaffraria

- List of conflicts in Africa

- Martini-Henry

- Military history of South Africa

- Scramble for Africa

- Shaka Zulu (TV series)

- Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or "Africa's 100 Years War")

- Zulu Kingdom

- Zulu War

References

[edit]- ^ "Zulu (1963)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Film Finance, Ltd. (Production Bond Company) Statement of Production Costs #15, week ending, 18 October 1963

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 360

- ^ "Film giants step into finance". The Observer. London, UK. 19 April 1964. p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stafford, Jeff. "Zulu". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ "The 100 best British films". Time Out. Retrieved 26 October 2017

- ^ "Michael Caine". Front Row. 29 September 2010. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon (2005). Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It: The Making of the Epic Movie. Sheffield, England: Tomahawk. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-95319-2-663.

- ^ a b Thompson, Howard (1 September 1963). "Stanley Baker: Peripatetic Actor-Producer; Genesis Provincial Debut". The New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ a b c Hall, Sheldon (19 January 2014). "The untold story of the film Zulu starring Michael Caine, 50 years on". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Hawksley, Rupert (22 January 2014). "Zulu: 10 things you didn't know about the film". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Stahl, Lesley (20 December 2015). "Michael Caine". 60 Minutes (television interview). Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ Caine, Michael (18 October 2021). "Michael Caine on Brexit, Boris Johnson and big breaks: 'I've done 150 movies. I think that's enough'". The Guardian (Interview). Interviewed by Xan Brooks.

- ^ James, Garry (6 July 2016). "The British Martini-Henry Rifle". Guns and Ammo.

- ^ Film Finance, Ltd. (Production Bond Company) Statement of Production Costs #15, week ending, 18 October 1963

- ^ Newsinger, John (July 2006). The Blood Never Dried: A People's History of the British Empire. Bookmarks Publications Ltd.

- ^ "Fact Sheet No. B3: The 24th Regiment and its local links". Museums of the Royal Regiment of Wales. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008.

- ^ "Zulu". Rorkes Drift VC. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Chadwick, G. A. (January 1979). "The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879: Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift". Military History Journal. 4 (4). The South African Military History Society/Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Popular Myths". Rorkes Drift VC. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Hale, Frederick (December 1996). "The Defeat of History in the film Zulu". Military History Journal. 10 (4). The South African Military History Society/Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b "James Henry Reynolds". Rorkes Drift VC. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Rorke's Drift 125-year anniversary". BBC News. 24 January 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Swaine, Jon (15 August 2008). "Battle to restore 'Zulu' hero Henry Hook's reputation". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Busting the myths of Rorke's Drift". readinggivesmewings.com. 2 December 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Row erupts over Newcastle's 'forgotten' VC winner William Allen who served at Rorke's Drift". Chronicle Live. 7 September 2004. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ "Colour Sergeant Bourne DCM". Rorkes Drift VC. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "An account by Lieutenant-Colonel Frank Bourne, OBE, DCM". The Listener. 30 December 1936. Retrieved 12 May 2016 – via Rorkes Drift VC.

- ^ "Zulu". Rorkes Drift VC. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ "Cpl. Ferdnand Christian Schiess".

- ^ Smythe, Graeme. "The Battle of Rorke's Drift, 22/23 January 1879". Isibindi Africa. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010.

- ^ a b Dovey, Lindiwe (2009). African Film and Literature: Adapting Violence to the Screen. Columbia University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780231519380. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

While interpretations of the film have been polarized between critics who claim that it is deeply anti-imperial and those who believe that it is racist (Hamilton and Modizane 2007), I want to briefly analyse the final sequence of the film to show that in treating the Zulus "equally" the filmmakers compromise an anti-imperial message of the film. ... the Zulu warriors have come back "to salute fellow braves". ... This final scene, however, is not historically accurate. ... The war was not fought on equal terms, due to the superior firearms of the British, and the filmmakers therefore require the Zulus to pay tribute to the British since it is only the Zulus who can authenticate the fairness of the war.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (8 July 1964). "It's British vs. Natives in Action-Filled 'Zulu'". The New York Times. p. 38.

- ^ "Zulu". Variety: 6. 29 January 1964.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (24 July 1964). "10,000 Zulus Bite the Dust". The Washington Post. p. B9.

- ^ Balliett, Whitney (18 July 1964). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 93.

- ^ "Zulu". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 31 (361): 23. February 1964.

- ^ "Zulu". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "Zulu Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis (20 May 1999). "Zulu". Ozus' Movie Reviews. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Kimon de Greef (2 June 2014). "The film Zulu, 50 years on: classic or racist?". This Is Africa. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

TIA (This is Africa): And did you get to watch it when it was finished?

MB (Mangosuthu Buthelezi): Censorship was terrible in South Africa, and the film, which showed white and black people fighting and killing each other, was banned for black audiences. The government had this silly attitude that the scenes of blacks killing whites would incite people to violence. But we requested permission for the Zulu extras who participated to see the film, and so a few special screenings were organised in Durban and some smaller KwaZulu towns. - ^ McEneany, Chris (6 February 2009). "Zulu Movie Review". AVForums. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Zulu: Michael Caine loses the plot, but wins the battle". The Guardian. 11 February 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "EMPIRE ESSAY: Zulu Review". January 2014.

- ^ "BLU-RAY REVIEW: "ZULU" (1964)". Cinemaretro.com. 12 April 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Heaven, Will (23 December 2014). "Zulu: is this the greatest ever British war film?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ O'Brien, Daniel (2017). Black Masculinity on Film: Native Sons and White Lies. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 9781137593238. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Flanagan, Jane. "Tribal chief defends Michael Caine film Zulu in racism battle". The Times. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon (2005). Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It: The Making of the Epic Movie. Sheffield, England: Tomahawk. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-95319-2-663.

- ^ "100 Greatest War Films : 10 to 6". Film4. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Coate, Michael. ""Zulu" 50th Anniversary". The Digital Bits.

- ^ Lipp, Chaz (5 February 2014). "Blu-ray Review: Zulu – Twilight Time Limited Edition". The Morton Report. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon (2005). Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It: The Making of the Epic Movie. Sheffield, England: Tomahawk. ISBN 978-0-95319-2-663.

- ^ Zulu at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Movie Classic: "Zulu" at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- ^ "Magazine cover". Jamesbooth.org. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Conte Collectibles – The Worlds Finest Toy Soldiers". Contecostore.com. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Leotta, Alfio (2015). Peter Jackson. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 164. ISBN 978-1501338557.

- ^ "Massacre at Ork's Drift Mega Display". The Stuff of Legends. 1 July 2000. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "UK Games Day '97 Display". White Dwarf. Vol. 218. pp. 99–71.

- ^ "The mystery of Sir Stanley and a 'fake' VC medal". Wales Online. 5 April 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (Reprint ed.). New York: Picador. pp. 89–108. ISBN 978-0312425791.

Bibliography

- Dutton, Roy (2010). Forgotten Heroes: Zulu & Basuto Wars including Complete Medal Roll. Infodial. ISBN 978-0-95565-544-9.

- Hall, Sheldon (2005). Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It: The Making of the Epic Movie. Sheffield, England: Tomahawk. ISBN 978-0-95319-2-663.

- Morris, Donald R. (1998). The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-30680-8-661.

External links

[edit]

- 1964 films

- 1960s historical adventure films

- 1964 war films

- British Empire war films

- British historical adventure films

- British war epic films

- 1960s English-language films

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films scored by John Barry (composer)

- Films about the British Army

- Films adapted into comics

- Films directed by Cy Endfield

- Films set in 1879

- Films set in South Africa

- Films set in the British Empire

- Films shot in South Africa

- Siege films

- War films based on actual events

- Works about the Anglo-Zulu War

- Zulu-language films

- Censored films

- 1960s British films

- Paramount Pictures films

- English-language historical adventure films

- English-language war films